politics

Former Lt. Gov. Bill Ratliff — 'father of Robin Hood' — reshaped Texas

Bill Ratliff’s influence on Texas government outlasted both his title and the politics that sidelined him

Published December 14, 2025 at 11:00am by John C. Moritz

The flags over the Texas Capitol flew at full staff last week. That's only notable because former Lt. Gov. Bill Ratliff died Monday at 89, long after his 15-year career as an elected official, most of it as a state senator representing a rural East Texas district, had come to an end. It's not unusual for the Texas and American flags to be lowered to honor the passing of a prominent leader or to mark a tragedy that shocks the sensibilities of the state.

Readers of a certain age and Texas political history junkies of average skill level and above will recall that Ratliff's two-year service as the 40th lieutenant governor came with an asterisk. Unlike the 39 before him and the two who followed, Ratliff was not elected in a statewide vote. Instead, he was chosen in a secret ballot of the Texas Senate to fill the vacancy left when then-Lt. Gov. Rick Perry ascended to the Governor's Mansion after George W. Bush was elected president.

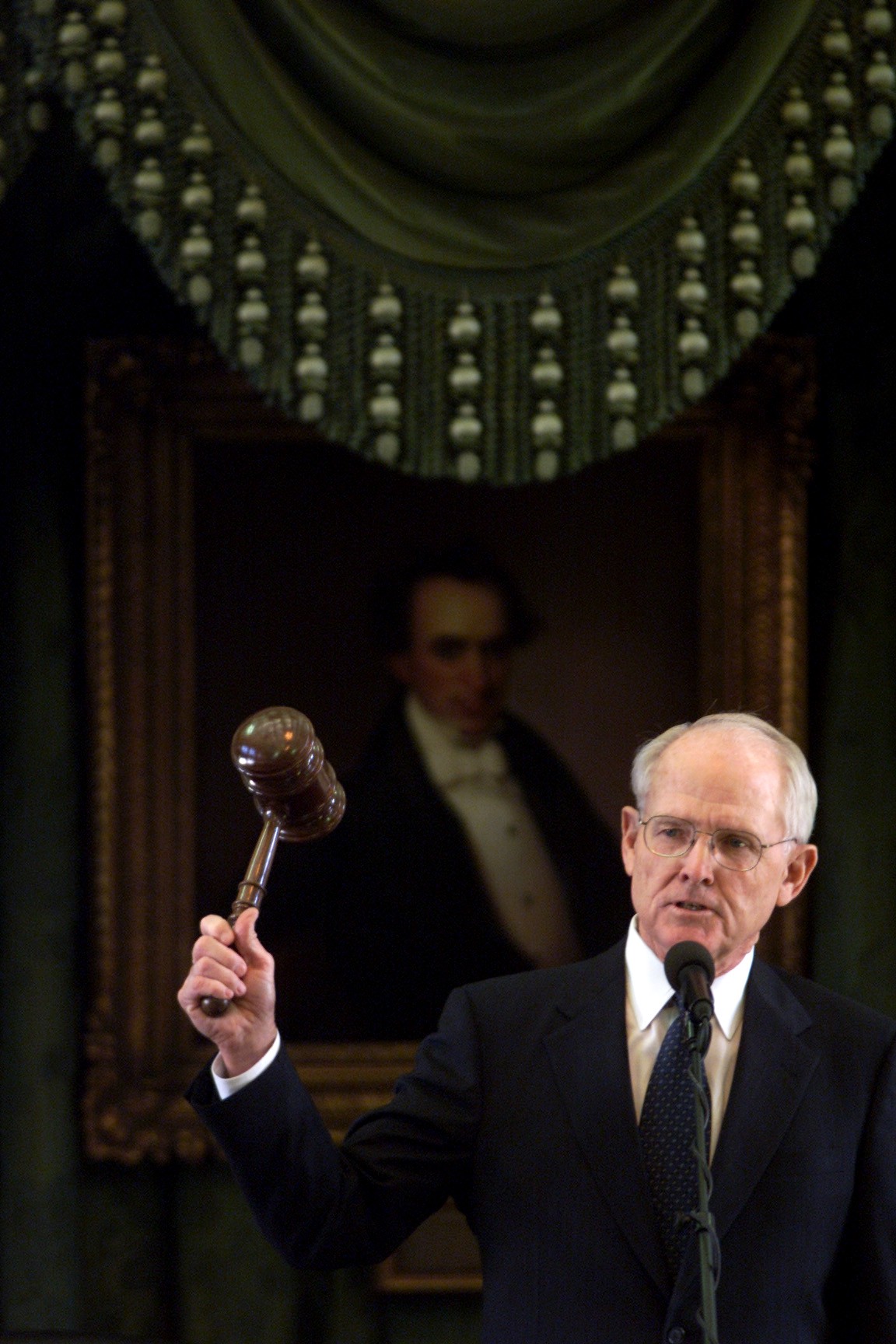

Lt. Gov. Bill Ratliff wields the gavel in the Texas Senate on the first day of the 77th legislative session at the Capitol in Austin on Jan. 9, 2001.

Ratliff's selection by his peers was hardly a fluke. He had served two teams as the powerful chairman of the budget-writing Senate Finance Committee and before that led the chamber's Education Committee, where it fell to him to craft a school finance system that would pass court muster and a divergent assortment of political agendas after the system existing at the time had failed in its constitutional obligation to provide an "adequate" education for each and every child enrolled in Texas' public schools.

For that, Ratliff became known as "the father of Robin Hood," the nickname for his plan forcing districts with robust property tax bases to send a portion of their revenue to districts with fewer resources.

But it was Ratliff's four years at the head of the Finance Committee that burnished his standing among his fellow senators. Having sway over billions of dollars in state spending is powerful and thankless at the same time. The money available to spend is finite; the demands for at least a share of it are not. That means the Finance Committee chair, in both rich times and lean, has to say "no" more often than "yes" to the endless parade of interest groups and to the very lawmakers the chair must ask to vote in favor of the budget.

The budgets Ratliff presented to the Senate passed without opposition. And his mastery over each detail in the spending documents and his intricate knowledge of the ins and outs of state government earned Ratliff the nickname "Obi Wan Kenobi," after the Jedi master from the "Star Wars" franchise.

When Ratliff became lieutenant governor, his task was to preside over a Senate divided 16-15 in favor of his fellow Republicans. And the Democrats came into that 2001 legislative session with feelings still raw because they were denied the opportunity in 1999 to bring a bill to the floor that would add stiffer punishment for violent crimes motivated by hate against people because of their race, religion or sexual identity.

The back story was that Bush, then gearing up for his presidential run in 2000, did not want to be in a position, were he to sign such a bill, in which he might be seen as buying into what was then called "the gay agenda." The thinking at the time was that social conservatives would turn on him in Republican primaries and in so doing dash his hopes to win the White House. Perry and Senate Republicans did what was needed to spare Bush that conundrum.

In 2001, most Senate Republicans who opposed the hate crimes legislation two years earlier opposed it again. But, led by the bill's sponsor, Sen. Rodney Ellis of Houston, Democrats were able to peel off enough Republicans to pass the bill. But that couldn't happen unless Ratliff agreed to bring it to the floor for a vote. And, persuaded that the votes were there to pass it, Ratliff brought it up.

Ratliff that session served in a dual capacity. He remained a senator, but as the chamber's presiding officer, he followed the House speakers' tradition of abstaining from votes on most matters. But on the hate crimes bill, he exercised his prerogative and voted yes. And that, and a handful of other actions he took as lieutenant governor, would come with a cost.

Ahead of the 2002 election cycle, Ratliff announced he would run for the office in his own right and give Texans the opportunity to ratify the decision made earlier by his fellow senators. It proved to be a short-lived endeavor. The same strain of conservative Republicans that might have turned on Bush over the hate crimes bill did turn on Ratliff.

That opposition, and the announced primary challenge by then-Land Commissioner David Dewhurst, a millionaire several times over and able to self-finance his campaign, helped persuade Ratliff to step aside. He instead returned to his role as a rank-and-file senator but remained something of an outcast Republican before resigning in 2004.

And that brings us back to the matter of how the flags at the Capitol were flown in the days after Ratliff's death. Gov. Greg Abbott has the authority to order the flags lowered anytime he believes circumstances dictate. He ordered them lowered after the assassination of conservative activist Charlie Kirk of Arizona in September and to mark the legacy of the late liberal U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 2020. They were also lowered after horrific mass shootings in Texas and elsewhere, and after the deadly Hill Country flooding on July 4.

The death in March of U.S. Rep. and former Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner was marked by flags at half-staff, as was this year's passing of Bruce Bugg, the longtime chairman of the Texas Transportation Commission. Abbott's office did not respond to a question about whether Ratliff's service to Texas merited the lowering of the flags, but the answer would appear to be self-evident.